Super Coral: Collaboration is Key to Testing Resilient Coral

Florida’s reefs are in crisis. Scientists are turning to Honduran corals for a lifeline.

Off the coast of Florida, coral reefs are struggling to survive. Rising ocean temperatures and mass bleaching events have left these vital ecosystems on the brink of collapse. But a team of researchers at the University of Miami is working to change that—with some unlikely collaboration from Honduras.

*All photographs taken by me unless otherwise noted

In 2023, a devastating marine heat wave swept across Florida’s waters, leaving nearly all coral in its wake bleached and vulnerable. The damage was so severe that it underscored the urgency of finding new ways to restore these reefs. For Professor Andrew Baker and his team, the search led them to Tela Bay in Honduras, a coastal region where corals appear to be thriving despite warming waters.

Dr. Baker directs the Coral Reef Futures Lab at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine Atmospheric, and Earth Science, focusing on the development and testing of methods to increase coral reef resilience.

“We needed to find corals that have a natural ability to survive in extreme heat,” Baker explained. “And Tela Bay gave us hope. The resilience we see there might be a key to saving Florida’s reefs.”

Baker and his graduate students collected hundreds of coral DNA samples from the Honduran waters, targeting species that showed exceptional resistance to temperature stress. They also brought back live coral fragments, including elkhorn and brain corals, which they plan to study and crossbreed with Florida corals. The goal is to produce hybrids that are better equipped to handle the realities of a warming ocean.

Florida’s reefs play a crucial role in protecting coastlines from storms and erosion, supporting marine biodiversity, and fueling local economies through tourism and fisheries. But with ocean temperatures reaching record highs, these ecosystems are struggling to keep up. Scientists estimate that without intervention, many coral species in Florida could disappear entirely within decades.

Lab Manager walking us through the coral spawning and DNA collection process

This collaborative effort between Honduran and Florida corals represents a bold new strategy in reef conservation. Once the coral fragments completed their journey to Miami, they were placed in a controlled hatchery environment at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. There, researchers are analyzing their genetic makeup and monitoring their spawning cycles. The hope is that by combining the genetic strengths of these heat-tolerant corals with Florida’s native species, researchers can create a new generation of corals capable of thriving in the face of climate change.

The stakes are high, but the scientists are optimistic. The success of this project could not only help restore Florida’s coral reefs but also offer insights into how other regions might adapt to rising global temperatures. By leveraging the natural resilience found in places like Honduras, researchers believe there’s still a chance to safeguard these critical ecosystems, and the communities that depend on them.

“This isn’t just about coral restoration,” Baker said. “It’s about creating a blueprint for resilience that could help protect marine ecosystems worldwide.”

Engineering the Future: Hybrid Reefs Are Changing Coastal Resilience

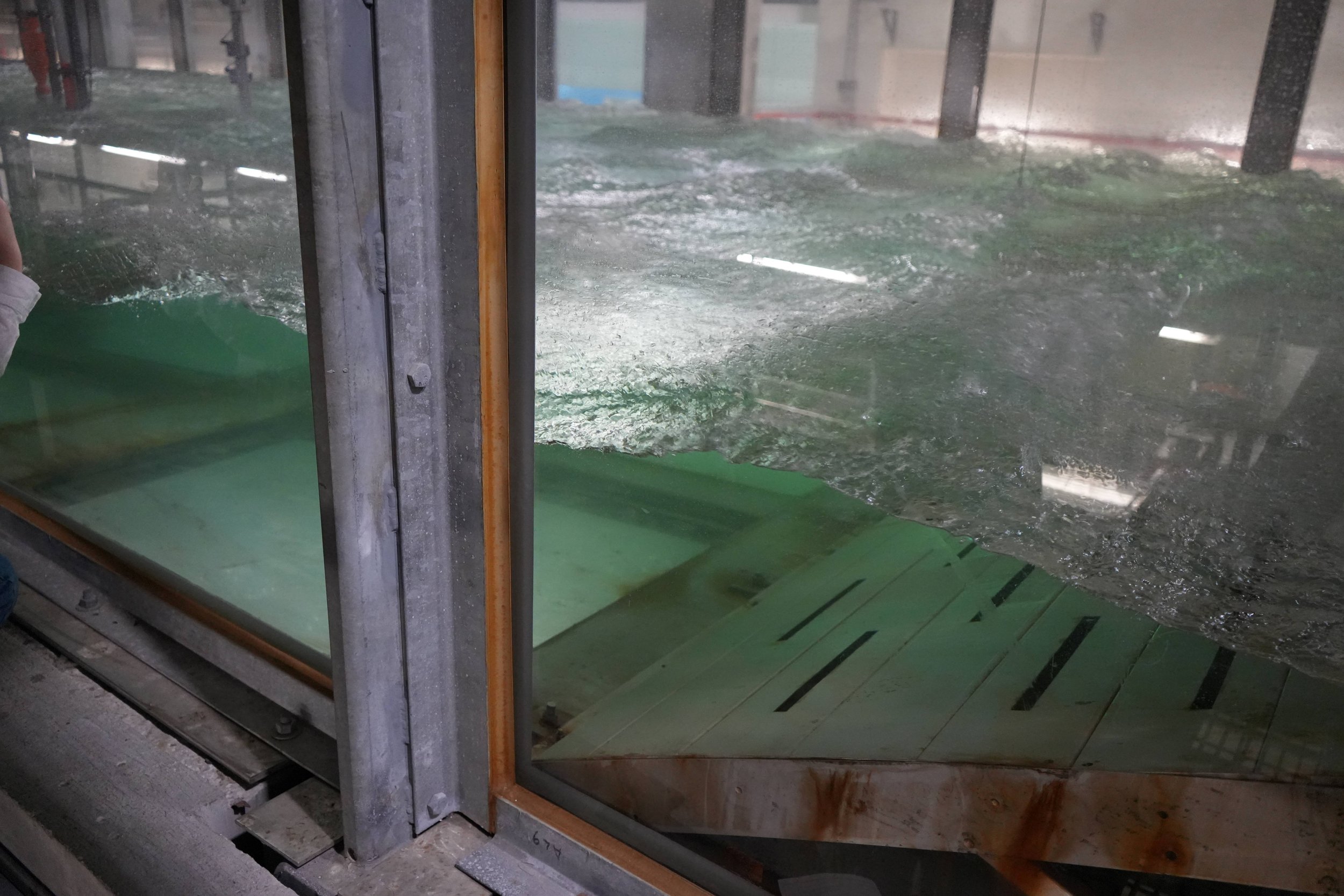

In addition to their work to identify resilient coral, Dr. Baker’s lab is spearheading SEAHIVES, a bold Miami-based project designed to revolutionize coastal defense. These next-generation hybrid reefs marry the protective power of artificial concrete structures with coral reef restoration. By combining cutting-edge structural designs, ecological engineering, and adaptive biology, the project aims to develop reef systems that can withstand climate stressors and other disturbances, while providing communities protection from coastal storm surge.

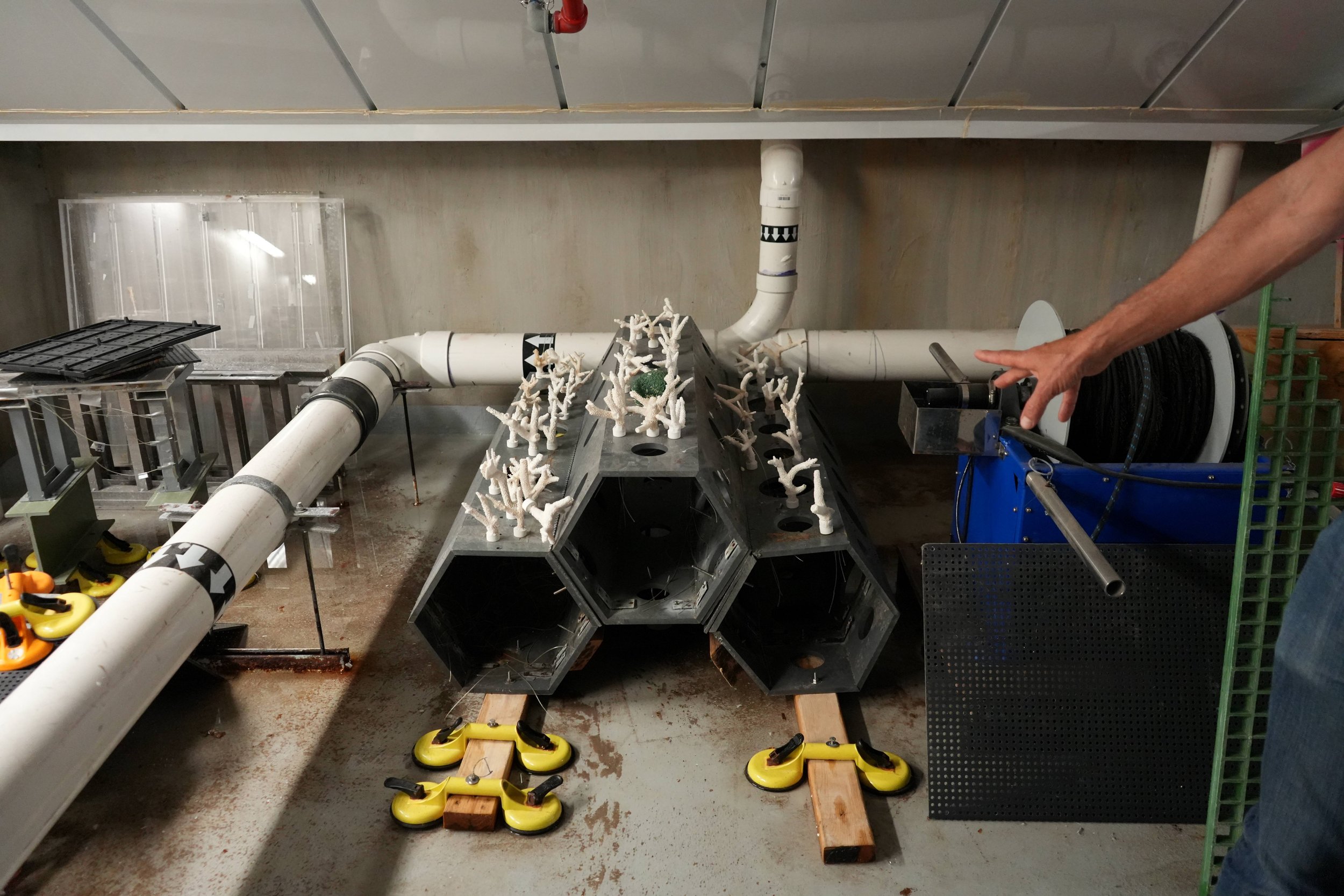

Think of SEAHIVE as a high-tech honeycomb for the ocean: its perforated hexagonal modules absorb wave energy, reducing erosion and flooding while doubling as a habitat for marine life. Made from low-alkalinity cement reinforced with non-corrosive materials, the SEAHIVE design is built to handle the wear and tear of marine environments while leaving a minimal ecological footprint.

After deploying the structures offshore, the lab populates the top of the structures with coral they think are most suited to withstand the heat. So far, the researchers seem optimistic, but there is more work to be done.

Hybrid reefs represents the future of coastal resilience, where engineered solutions work in harmony with nature to protect both people and the planet. The lab’s efforts alongside a large team at the University of Miami have their work cut out for them. But collaboration, both locally and overseas, is key to this climate solution.

Dr. Baker (left) explaining the value of SEAHIVES in coastal protection and the science-backed need for cities like Miami to invest in coral reefs as a climate resilience solution.